Last Friday, Nineteenth Century French Studies shared a wonderful conversation between Dr. Colin Foss and Prof. Nicholas White, about Foss’s new book The Culture of War: Literature of the Siege of Paris, 1870–71. During the presentation, Foss briefly mentioned a short story by Guy de Maupassant, “Deux Amis” (1883), set during the siege of Paris. As soon as the talk was over, I reread the story and immediately began translating it.

It’s a great story that takes the reader to one of Maupassant’s favorite places—the Seine just to the west of Paris—and shows it in a very different light, in comparison to stories he published around the same time, like “La Femme de Paul”, or “Une Partie de Campagne” (both published 1881), or Yvette (1884).

Below is my translated version of the text.

Two Friends

Paris was blockaded, starving, and grumbling. Sparrows were rare sights on the rooftops, and the sewers were empty. One ate whatever came to hand.

As he was walking morosely on a clear January morning along the outer boulevard, hands in the pockets of his uniform breeches, and his stomach empty, Monsieur Morissot, watchmaker by trade and homebody by circumstance, stopped short in front of a comrade he recognized as a friend. It was Monsieur Sauvage, an acquaintance from the water’s edge.

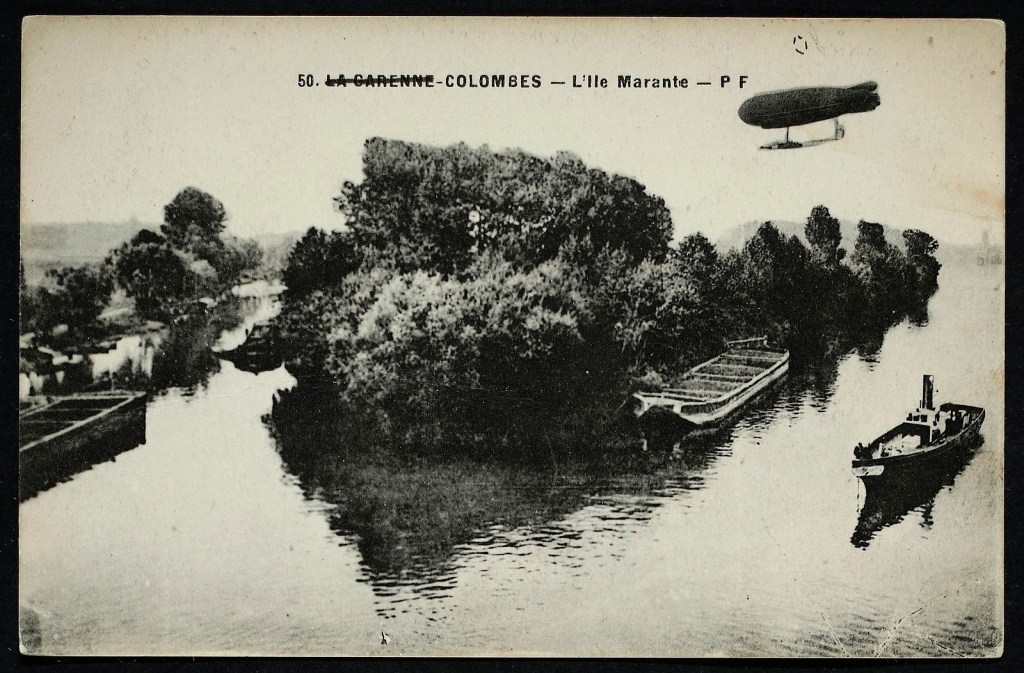

Every Sunday before the war, Morissot would set out at dawn, bamboo cane in one hand, a tin-plate box on his back. He took the train in the direction of Argenteuil, getting off at Colombes, then made his way to the Île Marante on foot. Scarcely arrived in that perfect spot, he would begin to fish; he would until nightfall.

Every Sunday he encountered there a roundish and jovial little man, Monsieur Sauvage, haberdasher of the rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, another fanatical fisherman. They often spent half a day together side by side, lines in their hands and their feet dangling above the current; and they had become fast friends.

Some days they wouldn’t speak. Sometimes they would chat; but they understood one another admirably without needing to say anything, having similar tastes and identical dispositions.

On spring mornings, around ten when the growing sunlight would raise a thin mist over the tranquil river that would flow along with the water, and poured the joyful season’s new warmth onto the two backs of those two immoderate fishermen, Morissot would sometimes say to his neighbor, “Well, what warmth!” and Monsieur Sauvage would answer, “I know nothing better.” And that alone was enough for them to understand and appreciate one another.

In the autumn, toward end of day, when the sky is bloodied by the setting sun, purples the river, sets the horizon aflame, made the two friends glow red as fire, and gilded the reddenening trees, already trembling with a shiver of winter, Monsieur Sauvage would smile at Morissot and say, “What a spectacle!” And Morissot, marveling, and without taking his eyes from his float, would say, “Better than the boulevard, hey?”

As soon as they recognized one another, they energetically shook hands, moved to be finding one another in such different circumstances. Letting out a sigh, Monsieur Sauvage murmured, “Look at how things have turned out!” Morissot, very morose, moaned, “And what weather! Today’s the first nice day of the year.”

The sky was, in fact, completely blue, and full of light.

They began walking side by side, dreaming and dismal. Morissot began again, “And fishing? hey! what a good memory!”

“Monsieur Sauvage asked, “When will we ever go back?”

They entered a little café and together drank an absinthe; then they began roaming the pavements.

Morissot stopped suddenly, “Another glass of green, hey?” Monsieur Sauvage consented, “At your service.” And they entered a wine merchant’s shop.

They were well and giddy by the time they left, unsteady as one is, having filled their empty stomachs with alcohol. It was warm. A caressing breeze tickled their faces.

Monsieur Sauvage, who was now completely drunk on the warm air stopped:

“What if we went?”

“Went where?”

“Well, fishing.”

“But where, though?”

“But on our island. The French outpost is near Colombes. I know the Colonel Dumoulin; they’ll let us pass, no problem.”

Morissot trembled with desire: “Done. I’m in.” And they went their separate ways to find their tackle.

An hour later, they were walking side by side on the high road. Then they reached the villa that the colonel occupied. He smiled at their request and gave in to their fancy. They began to walk again, armed with a password.

Soon they passed the outpost, crossed abandoned Colombes, and found themselves at the edge of little vineyards that sloped toward the Seine. It was about eleven o’clock.

Across from them, the village of Argenteuil seemed dead. The heights of Orgemeont and de Sannois dominated the whole countryside. The great plain that reaches all the way to Nanterre was empty—completely empty—with its bare cherry trees and its gray earth

Monsieur Sauvage, pointing out the summits with his finger, whispered, “The Prussians are right up there!” and dread paralyzed those two friends, facing the deserted land.

“The Prussians!” They had never even seen one, but they had felt them for months, all around Paris, ruining France, pillaging, massacring, starving, invisible and all-powerful. And a sort of superstitious terror added to the hatred that they had for that unknown and victorious nation.

Morissot stammered, “Well! if we run into them?”

Monsieur Sauvage answered, his Parisian mockery showing itself in spite of everything:

“We’ll offer them a fry-up.”

But they hesitated to venture out into the countryside, intimidated by the broad horizon’s silence.

At last, Monsieur Sauvage made up his mind. “Come on, let’s go! but with care.” And they went down through a vineyard, bent double, crawling, using bushes to cover themselves, their eyes darting, ears reaching out.

One strip of open ground remained to cross to reach the bank of the river. They began to run; and as soon as they had reached the bank, they nestled down in the dry reeds.

Morissot glued his cheek to the ground to listen for anyone marching nearby. He heard nothing. They were well and alone.

They reassured themselves and began fishing.

Across from them the abandoned Île Marante hid them from the other bank. The little house of the restaurant was shuttered, looking as though it had been abandoned for years.

Monsieur Sauvage took the first gudgeon, Morissot the second, and from then on, they raised their lines with a little silvered creature thrashing at the end of their hook: a truly miraculous expedition.

They delicately inserted the fish into a pouch of tightly-woven netting dipped in the water by their feet. And a delicious joy penetrated them, the joy that takes hold of one in rediscovering a beloved pastime of which one has long been deprived.

The good sun poured its heat between their shoulders; they were listening to nothing; they were thinking of nothing; they knew nothing of the rest of the world; they fished.

But suddenly a dull noise seemed to come up from beneath the earth, making the ground shake. The cannon had begun again to thunder.

Morissot turned his head, and beyond the bank, he saw on the left, the great silhouette of Mont-Valérian, that sported a white egret on its brow, having just spat out a puff of pale smoke.

Straightaway a second jet of smoke departed from the summit of the fortress; and a few instants later, a new detonation growled.

Others followed, and from moment to moment, the mountain tossed out its deadly breath, exhaling its milky vapors that rose slowly into the calm sky, creating a cloud overhead.

Monsieur Sauvage shrugged his shoulders. “Looks like they’re starting in again,” he said.

Morissot, who was anxiously watching the feather on his float dip intermittently beneath the surface was suddenly taken with the rage of a placid man man against the madmen who fight in that manner. He growled, “Stupid way to kill one another.”

Monsieur Sauvage answered, “Worse than animals.”

And Morissot, who had just taken an ablet, declared: “And I tell you, it’ll be this way as long as there are governments.”

Monsieur Sauvage stopped him, “The Republic wouldn’t have declared the war…”

Morissot interrupted him, “With kings you have the war without. With the Republic, you have the war within.”

Quietly they began to discuss the situation, solving all the great political questions with the healthy reason of gentle and limited men, agreeing that to one extent or another, that one would never truly be free. And Mont-Valérian thundered without rest, demolishing French homes with its cannonballs, burning lives, crushing souls, putting an end to a good many dreams, a good many hoped-for joys, and opening in the hearts of women and in the hearts of girls, in the hearts of mothers, over there, and in other countries, suffering that shall never end.

“That’s life,” declared Monsieur Sauvage.

“Better say, that’s death,” Morissot said, laughing.

But they trembled, frightened, feeling something had come up behind them; and turning their eyes, they saw four men sanding at their shoulders, four bearded and armed men, domestic servants in livery, capped with flat helmets, and aiming the muzzles of their rifles toward them.

The two fishing lines fell from their hands and began descending the river.

In seconds, they were seized, tied up, and led away, tossed into a barge and carried off to the island.

Behind the house they had believed abandoned, they spotted a good twenty German soldiers.

A sort of hairy giant, who sat straddling a chair, smoking an large porcelain pip asked them in excellent French, “Well, gentlemen, did you have a good outing?”

A soldier dropped at the officer’s feet the net full of fish, which he had taken care in bringing back. The Prussian smiled, “Hey, hey! I see that it wasn’t going poorly. Now listen to me and don’t you worry.

“As I see it, you two are spies sent to keep a lookout for me. I have captured you, and I shall shoot you. You were pretending to fish, so as to better hide your designs. You have fallen into my hands. So much the worse for you. That’s war.

“But as you must have come from an outpost, you must assuredly have been given a password in order to return. Give me that password and I shall show you mercy.”

The two men, livid, side by side, their hands twitching from a gentle nervous tremor, were silent.

“The officer said again, “No one will ever know, you’ll go home in peace. Your secret will vanish with you. If you refuse, it’s death, and straight away. So. Choose.”

They remained immobile, not opening their mouths.

The Prussian, still calm, said again, holding out his hand toward the river: “Remember that in five minutes you will be at the bottom of this water. Five minutes! You must have relatives?”

Mont-Valérian thundered still.

The two fishermen remained standing and silent. The German gave orders in his language and then moved his chair, so not to be farther away from his prisoners. Twelve men came to stand twenty paces away, rifles by their feet.

The officer began again, “I shall give you one minute, not two seconds more.”

Then he got up suddenly, came toward the two Frenchmen, took Morissot under his arm, led him aside, said to him in a low voice, “Quick, tell me the password? Your comrade will never know, I’ll pretend to have changed my mind.”

Morissot didn’t answer.

The Prussian led Monsieur Sauvage away and asked him the same question.

Monsieur Sauvage didn’t answer.

They found themselves again side by side.

And the officer began to command. The soldiers raised their weapons.

By chance, Morissot’s gaze fell upon the net full of gudgeons lying in the grass a few steps away.

A ray of light made the heap of still-moving fish glimmer. And a weakness took hold of him. In spite of his efforts, his eyes filled with tears.

He stammered, “Farewell, Monsieur Sauvage.”

Monsieur Sauvage answered, “Farewell, Monsieur Morissot.”

They clasped their hands, their bodies speaking from head to toe with invincible tremors.

The officer cried, “Fire!”

Twelve shots came as one.

Monsieur Sauvage fell in a heap onto his nose. Morissot, taller, swayed, pivoted, and fell crosswise over his comrade, face toward the sky, while gouts of blood pumped through the tunic, shredded across his breast.

The German gave new orders.

His men dispersed, then returned with ropes and stones that they tied to the feet of the two dead men; then they carried them to the bank.

Mont-Valérien never ceased its growling, capped now with a mountain of smoke.

Two soldiers took Morissot by his head and legs; two others seized Monsieur Sauvage in the same manner. The bodies momentarily swayed with force, were thrown far out, drawing an arc, then fell standing up into the river, the stones dragging them down feet-first.

The water splashed back, boiled, trembled, then quieted, while little waves reached the other side.

A little blood rose to the surface.

The officer, still serene, said in a low voice, “Now it’s the fish’s turn.”

He went back toward the house.

And suddenly he saw the net of gudgeons in the grass. He picked it up, examined it, and smiling, cried, “Wilhem!”

A soldier in a white apron came running. And the Prussian tossing him the catch of the two men he’d just had shot, commanded, “Fry me these little creatures straightaway while they’re still alive. That will be delicious.”

Then he returned to smoking his pipe.